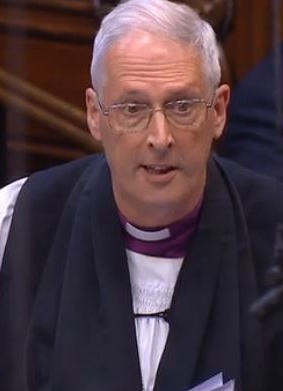

On 7th June 2023, during a committee debate on the Illegal Migration Bill, the Bishop of Southwark spoke in support of the Bishop of Durham’s amendment 78, which would allow exceptions to the bill’s proposed ouster of judicial review during the first 28 days of detention, for vulnerable individuals such as children, pregnant women, and those with mental health issues:

The Lord Bishop of Southwark: My Lords, I will speak to Amendment 78, tabled by the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Durham, who is unable to be here at this early hour. I know that he is grateful to the noble Baronesses, Lady Lister and Lady Neuberger, for their support.

A statutory regime of clinical screening for people at risk of harm in detention and for healthcare professionals to be able to report concerns to the Home Office has been a cornerstone of safeguarding in immigration detention since 2001—and rightly so. This amendment looks to ensure that this process does not become inconsequential by preventing the necessary legal oversight of detention decisions. Given the technical nature of the issues relating to medical reporting in detention centres, I will focus my comments on the context of this amendment and set out a few key questions for the Minister.

The harmful impact of being in detention on people’s mental health is widely evidenced. Professor Mary Bosworth’s literature review for Stephen Shaw’s 2016 Review into the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons summarised that evidence. She concluded:

“Literature from across all the different bodies of work and jurisdictions consistently finds evidence of a negative impact of detention on the mental health of detainees”.

This conclusion should not be set aside. It is most acute for those with pre-existing vulnerabilities. Given that, and the limitations of treating mental illness in detention, it is current Home Office policy not to routinely detain highly vulnerable people, including those with pre-existing mental illnesses and survivors of torture. Decisions to detain must be consistent with detention policies, in particular the adults at risk policy. This policy has statutory force under Section 59 of the Immigration Act 2016. The Government stated then that this policy would introduce into detention decision-making a clear presumption that people who are at risk should not be detained.

The right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Durham has, I believe, thanked the Minster personally for the opportunity to visit two immigration removal centres—visits he greatly valued. Officials and operational staff alike spoke to him of how Shaw’s recommendations have filtered through to every level of working, while recognising that improvements are still to be made. A key component of this is the statutory duty of medical staff to provide clinical safeguarding reports, known as rule 35 or rule 32 reports, where it is believed that detention may cause significant harm to an individual. These are then brought to the attention of those with direct responsibility for authorising detention.

How will this system of detention review on medical grounds be impacted by the provisions in the Bill? Do the Government agree with Stephen Shaw, the adults at risk policy and former ministerial colleagues that those whose care and support needs make it particularly likely that they would suffer disproportionate detriment from being detained would generally be considered unsuitable for immigration detention?

I shall of course listen carefully to the Minister’s answer, but the Bill suggests that the answer is no. By refusing to allow those who are detained to challenge their detention during the first 28 days by way of judicial review, there is no longer a clear presumption that the vulnerable will not be detained. The adults at risk policy provides that vulnerable adults at particular risk of harm in detention should not normally be detained and can be detained only when immigration factors outweigh the presumption to release, but the Bill legislates that the immigration factors at play, namely the Secretary of State’s new duty to detain and deport, will supersede this. If I am incorrect in this assumption, I shall be happy for the Minister to state the true position.

Judicial review is a key mechanism to challenge the tension where professional evidence of medical harm is believed to have been given insufficient weight. In this situation, without recourse to the courts a vulnerable person would be at risk of clinical harm from continuing detention. I appreciate that Rule 35 is a reporting mechanism, not an automatic method of release for an individual in detention, but without legal safeguards, detention for whom it poses a greater risk of medical harm will almost certainly be guaranteed. This is not merely conjecture: the High Court has found a number of breaches of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights in relation to the detention of severely mentally ill people and found that continued detention would have amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment.

If the Bill proceeds in its current form, what weight will the Home Secretary give to medical evidence from professionals, given that detention decisions will be entirely at her discretion and withheld from independent scrutiny? The ability to judicially review the lawfulness and reasonableness of decisions to detain is particularly important given recent independent evidence showing that safeguarding policies are not consistently followed. This concern has been raised often by the independent chief inspector.

Given that the Government have been honest in accepting that improvements are still to be made to safeguarding systems to identify the most medically vulnerable in detention, I ask the Minister why disqualifying those with a clinical report from judicially reviewing their detention was deemed an acceptable risk. Stephen Shaw labelled the adults at risk policy in his progress report as “a work in progress”. How will the Government ensure that this further progress is not halted entirely by the Bill?

Amendment 78 would make an exception to the general ouster of judicial review during the first 28 days of detention where a person has been the subject of a report from a medical practitioner. To be clear, this is where the Home Office has evidence that a person’s health is likely to be injuriously affected by continued detention, they have suicidal intentions or there is concern that they may have been a victim of torture. It is hard to conceive of a more vulnerable grouping, where the stakes are higher, when considering detention.

I fear that preventing any means of legal challenge for those in a very dangerous and precarious medical state could be a disaster waiting to happen. I therefore agree with the Royal College of Psychiatrists that:

“The Bill is not compatible with the fundamental medical principle of doing no harm”.

For that reason I urge the Government to consider the amendment tabled by the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Durham and the safeguarding issues it highlights with due care.

Extracts from the speeches that followed:

Lord Ponsonby of Shulbrede (Lab): My noble friend Lord Bach raised important questions in introducing this group and I look forward to the Minister’s answers to those questions. I could have quoted from the Bar Council, but the noble Baronesses, Lady Ludford and Lady Bennett, did so very effectively. I thought that the intervention of the noble Baroness, Lady Neuberger, supported by the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Southwark and my noble friend Lady Lister, was particularly poignant, given her experience of hospitals, people with suicidal ideation and the increased vulnerability of the people we are dealing with. That point was picked up by the noble Lord, Lord German.

I look forward to the Minister’s response to this group. We are talking about extremely vulnerable people. I know that this is rather abstract in the law and how the law is interpreted, but I think that the whole Committee is conscious of the vulnerability of these people.

Lord Murray of Blidworth (Con): Amendment 78, spoken to by the right reverend Prelate the Bishop of Southwark, would provide exceptions to the general ouster of judicial review during the 28 days of detention for a person for whom the Secretary of State has received a medical report evidencing their vulnerability to suffering harm in detention, including victims of torture or trafficking, pregnant women and those with mental health conditions.

The Home Office recognises that some groups of people can be at particular risk of harm in immigration detention and it already operates a bespoke policy that specifically considers all levels of vulnerability in immigration detention. As I said during the debates on previous groups, the policy on adults at risk in immigration detention, in an updated form, will continue to apply where detention decisions are made for those in the scope of the Bill, including where a medical report has been provided. In accordance with the policy, vulnerable people will be detained only where the evidence of vulnerability in their case is outweighed by immigration considerations. I assure the right reverend Prelate that this balancing process will not change as a result of the Bill.

You must be logged in to post a comment.